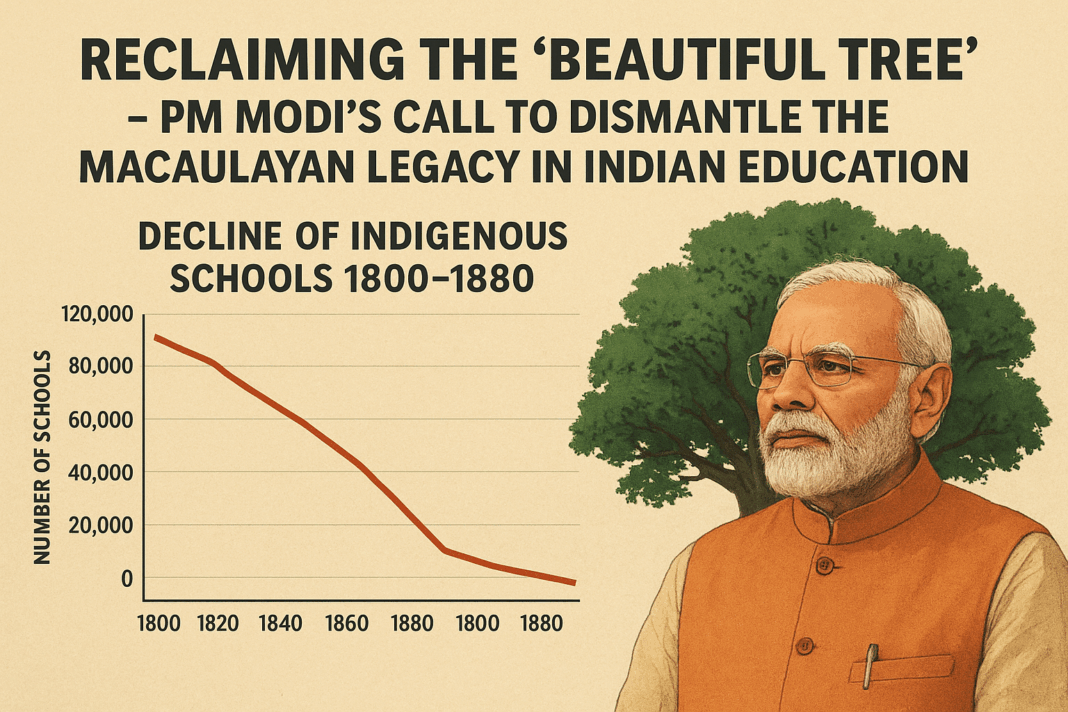

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s recent address at the sixth Ramnath Goenka Lecture has reignited a longstanding discourse on the colonial transformation of Indian education. Calling upon the nation to “free ourselves from the mindset of slavery that Macaulay imposed on India” by 2035, the bicentennial of Thomas Babington Macaulay’s infamous Minute on Education, the Prime Minister has placed the decolonisation of knowledge systems at the centre of India’s developmental vision.

Macaulay’s Minute: Colonial Intent and Its Instruments

On February 2, 1835, Thomas Babington Macaulay, as a member of the Governor-General’s Council, presented his Minute on Education, a document that fundamentally altered the trajectory of Indian learning. Macaulay’s contempt for indigenous knowledge was categorical and unapologetic. He declared: “I have no knowledge of either Sanscrit or Arabic. But I have done what I could to form a correct estimate of their value… I have never found one among them who could deny that a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia.”

This sweeping dismissal extended to historical scholarship, with Macaulay asserting that “all the historical information which has been collected from all the books written in the Sanscrit language is less valuable than what may be found in the most paltry abridgments used at preparatory schools in England.” Such pronouncements, delivered without proficiency in either Sanskrit or Arabic, reflected not scholarly assessment but colonial hubris designed to delegitimise millennia of Indian intellectual tradition.

The Minute‘s most consequential articulation, however, concerned its stated objective: “We must at present do our best to form a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern,—a class of persons Indian in blood and colour, but English in tastes, in opinions, in morals and in intellect.” This explicit agenda to create a culturally alienated intermediary class between colonial administrators and the Indian masses remains the foundational critique of what is now termed the “Macaulayan mindset.”

Gandhi’s Lament and Dharampal’s Documentation

The devastation wrought by this policy was powerfully articulated by M K Gandhi during his 1931 address at the Royal Institute of International Affairs: “I say without fear of my figures being challenged successfully, that today India is more illiterate than it was fifty or a hundred years ago… the British administrators, when they came to India, instead of taking hold of things as they were, began to root them out. They scratched the soil and began to look at the root, and left the root like that, and the beautiful tree perished.”

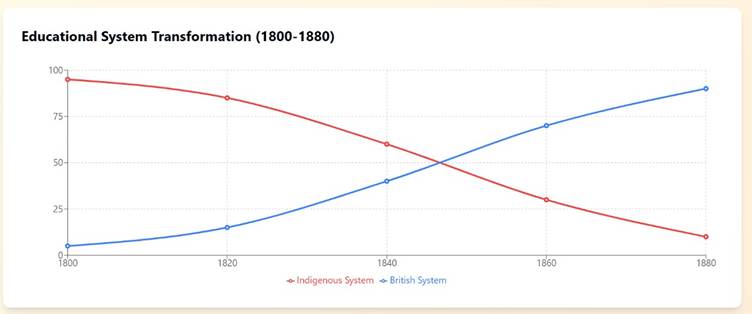

This metaphor of the “beautiful tree” was later substantiated through rigorous archival research by Dharampal, whose seminal work The Beautiful Tree: Indigenous Indian Education in the Eighteenth Century marshalled extensive statistical evidence from British colonial surveys themselves. The data revealed a remarkably inclusive and widespread educational ecosystem that contradicts persistent narratives of pre-colonial illiteracy and caste-based exclusion.

William Adam’s survey of Bengal and Bihar (1835–1838) documented approximately 100,000 village schools, nearly one school per 450 people. Crucially, Brahmins and Kayasthas nowhere formed more than 40 percent of the student population, while in two Bihar districts, they constituted merely 15 to 16 percent. The survey further noted that 674 scholars from the lowest sixteen castes attended native schools, compared to only 86 in missionary institutions.

The Madras Presidency survey (1822–1826) conducted under Governor Thomas Munro, who himself observed that “every village had a school”—produced equally striking figures. Students from Shudra communities constituted approximately 65 percent of enrolments, while Brahmins, Kshatriyas, and Vaishyas comprised only 24 percent. In Bellary district, Shudra students numbered 63 percent against 33 percent from upper castes; in Malabar, the ratio stood at 54 percent Shudra to 20 percent upper caste.

Contemporary Significance

PM Modi’s invocation of this history serves to contextualise the National Education Policy’s emphasis on instruction in local languages, not as linguistic chauvinism, but as recognition that nations such as Japan, China, and South Korea “adopted many western practices but never compromised on their native languages.” The Prime Minister clarified that the government is “not opposed to the English language but firmly supported Indian languages.”

The call to liberate Indian consciousness from colonial psychological conditioning by 2035 represents an invitation to critically re-examine educational foundations established nearly two centuries ago. As Dharampal concluded, understanding “what existed and of the processes which created the irrelevance India is burdened with today, in time, could help generate what best suits India’s requirements and the ethos of her people.”

Fig: A graphic visualization of the decline of the indigenous schools between 1800-1880, following the policy shift advocated in Macaulay’s minute. Based on the data found in Dharampal’s pioneering work, “The Beautiful Tree” (graphic generated using Claude AI).